Portrait

Detours to local knowledge

When Kuno Nüssli's Container DS found its way into the MAGAZIN range in 2011, nobody would have dreamed that the product would one day become one of the bestsellers in the range. And the success story continues - with the AIR, a version made of perforated sheet metal. We visited the universal creative Kuno Nüssli and his container in Basel.

Text: Jochen Overbeck

Kleinbasel would make a good motif for a hidden object book by the recently deceased Ali Mitgutsch. The Basel district on the east side of the Rhine is lively in the best sense of the word. At the old barracks, a painter offers his pictures for sale, colorful and naive. Young urban professionals sit in front of Café Frühling and indulge in flat white and blackberry tart. On Klybeckstrasse, a mother calls her child to order who doesn't stop at the crossing on her pedal bike. And if you turn left once and then again and enter the inner courtyard of the house at Breisacherstraße 64 through the driveway, where an old delivery van is parked, you find yourself in the workshop community, where Kuno Nüssli has also been working since 1997. What would Mitgutsch paint of the Swiss designer's props? Perhaps a few of the plywood parts he uses to build his boats. Perhaps also the old metal barrel in the workshop cellar; Nüssli sometimes uses it to test his paint gun; it looks a little as if Jackson Pollock and Rupprecht Geiger had made common cause. Perhaps also the radio, which Nüssli turns up to maximum volume even when the music is dubious, or one of the work tables in the bright studio-meets-office room on the upper floor, whose creative chaos ranges from paint fans to Leitz folders and which unpretentiously report that work is being done here.

The Container DS

One thing would certainly be seen in the Wimmel book: The Container DS, which stands in Nüssli's realm in completely different colors and shapes - from the "half portion" available as a FLAT, which gives an ensemble of several specimens unimagined dynamism, to the classic, which sometimes does what it does best in subtle white, sometimes in bright sulfur yellow and sometimes in gaudy telemagenta: Creating space for everything that needs space. The DS, which is modeled on the classic maritime containers, first performed this task in 2008 for the Basel art archive "dock:". In the same year, Nüssli exhibited it at the "Blickfang" design fair. MAGAZIN was immediately enthusiastic and decided to include the container in its program. After two years of development work, the time had come. Today, the DS - which, by the way, is manufactured in the factory of Oskar Zieta, also a MAGAZIN-Designer, is a classic in the program.

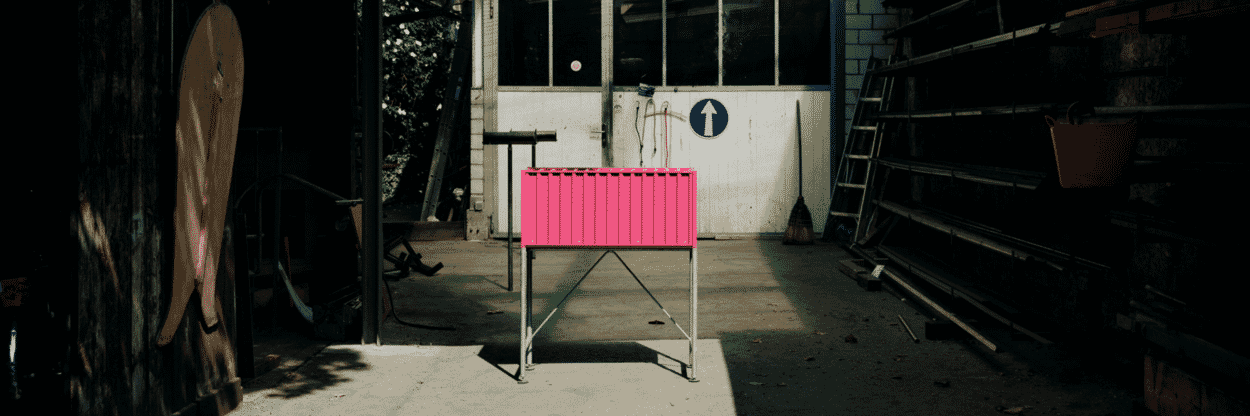

THE CONTAINER DS AIR

This collaboration, which has been going on for thirteen years, is now being extended: AIR is the name of the latest addition to the DS family. And of course AIR is also here in Nüssli's studio. If you creep around it, bend down a bit to admire the light that first enters the room through the large workshop windows and then enters the interior of the container through the small sheet metal holes, it quickly becomes clear: Nüssli and the Magazin-Team have carried out a product remix here that definitely interferes with the DNA of the furniture. The "close flap, all's well" principle has been replaced - yes, by what, actually? Openness? No, whatever the inclined user stows in the container, it is not readily recognizable. Rather, it is the allure of foreboding that AIR plays with. Who came up with the idea? "I think it was Oskar. Or was it all of us in a joint conversation? I can't even say exactly anymore!" says Nüssli.

Nor is it of too much importance, because AIR, despite the intrusion, seems like a compelling derivative of the classic while opening up all sorts of reference fields. The works of the French designer Mathieu Matégot come to mind, who from the 1950s used the material perforated sheet metal for armchairs, bar carts, even plates, and the wall shelves of Dutchman Tjerk Reijenga for Pilastro. But perhaps also: server cabinets that allow air to circulate. Kuno Nüssli smiles when people tell him about these associations, because his are different. He had to think, for example, of luminaires and their fascias, since he once worked for the luminaire manufacturer Baltensweiler AG.

"I think perforated metal is just a beautiful material," he says. "And I think for the container it works extremely well. As a solitaire, but also in combination with the regular container." He talks about possible uses, such as a home bar (unfortunately, MAGAZIN rejected the second floor with integrated lighting that Nüssli wanted for this purpose). Then the designer shows that optical effect that you experience if you look at the container long enough in the backlight and from a short distance: "If you see through the front perforated sheet the rear one, a regular third pattern results. Moiré is what this effect is called; you're actually more familiar with it from the textile world, for example, when different layers of a curtain fabric overlap. It's optical interference."

A life that runs in curves

Kuno Nüssli is - well, perhaps a dreamer. But when he talks about this seemingly simple container, it quickly becomes clear how much there is in this man. He completed an apprenticeship as a cabinetmaker at the end of the 1980s, only to switch materials soon afterwards, moving away from wood and towards metal in particular. He continued his education from 1993 onwards, studying interior design and building design, which led to him being responsible for the design and implementation of Basel's used glass collection points for three years, 40 of which he set up. He assisted the visual artist Pipilotti Rist and was later a graphic design intern at MetaDesign - "But only when Erik Spiekermann was already out of there," he says and laughs, as the aforementioned is also a good friend of MAGAZIN. He then worked as a graphic designer before turning back to furniture under the name kunotechnik.

So it's a career made up of detours, but that's all right, because detours increase local knowledge. Even today, Nüssli's life is one that follows curves. For private customers, he has a few pieces of furniture in his range that are made of colorful square steel; perhaps best known is the Anana bed. For his own pleasure, he has been building and restoring his boats for many years. He also took the next generation under his wing - he taught the preliminary course at the Basel School of Design; 16- and 17-year-olds had to deal with not-so-easy questions such as "What is a concept?". He was here in the workshop two days a week. Sometimes the doorbell rang, because MAGAZIN has no stores in Switzerland. "This is my showroom. People come by here, get a coffee and can look at and touch the container."

This makes sense, because the container shows its advantages especially when it is in use. At times, it keeps a low profile and is a quiet work and storage animal. Sometimes it shines and becomes a statement piece. A side note: In the evening, this becomes even clearer. The author is invited to dinner at Nüssli. For the first time this year he cooks his traditional summer pasta with tomato, basil and mozzarella as well as Swiss beer, and a glance at the apartment on the other side of the Rhine shows: Nüssli lives with and from his furniture, the container can be found in all variations - even in the children's rooms. Are they happy with their father's furniture? "It's okay," says the son. Nüssli is constantly rethinking the container in his head. Thinks about new colors, surfaces and materials and dreams beautiful dreams: "Sometimes I imagine a small crane," he says. "A miniature version of the ones you have in the cargo port. That could then move the individual containers." Would that serve a purpose? Well, it would have to be tried out, but it can't be ruled out. In any case, it would make an excellent picture in a Wimmel book.

Pictures: Lena Giovanazzi

From our range

Discover more designers

Globalization, says Stefan Diez, is not a bad thing per se. But if it only leads to cheap production, it prevents innovation and destroys the know-how of local companies.

The young designer Julia Dichte has developed a contemporary table linen series for MAGAZIN. EQUIPE is produced by a French weaving mill.

When architect and designer Michael von Matuschka designs, he is not concerned with aesthetic self-realization, but with the question of how we actually want to live.

.png?profile=kurator_32)

.png?profile=kurator_1250)

.png?profile=kurator_32)

.png?profile=kurator_1250)

.png?profile=kuratorteaser_32)

.png?profile=kuratorteaser_1250)

.png?profile=kuratorteaser_32)

.png?profile=kuratorteaser_1250)