In praise of the fugue

Anything but nothing: the joint is an indispensable design element in architecture and design, it separates and connects, provides precision and atmosphere. In the context of current debates on recycling and reuse, the joint is now gaining a whole new relevance.

Text: Markus Frenzl

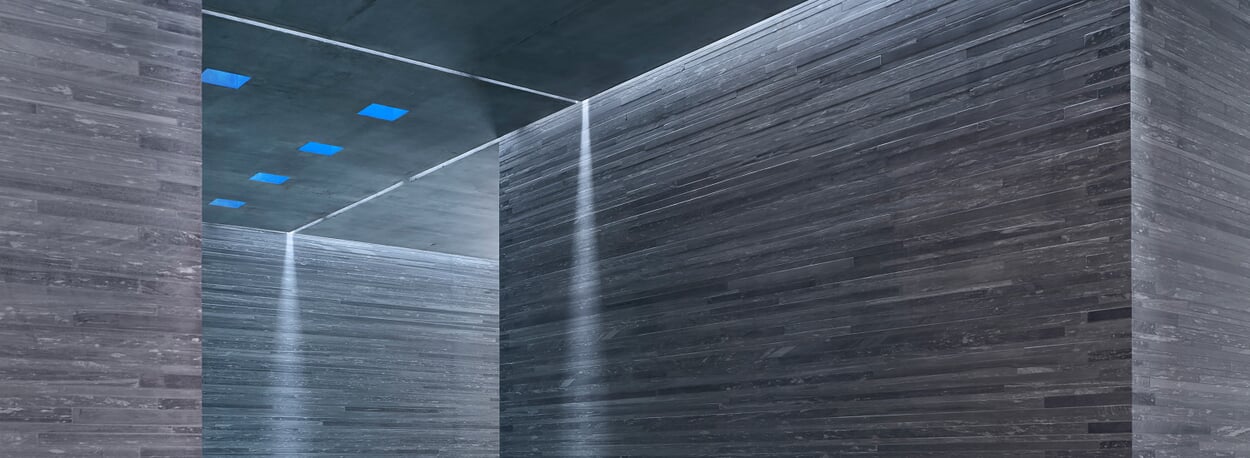

Before Therme Vals opened in Graubünden in 1996, it is said among architecture fans that the quality-obsessed Swiss architect Peter Zumthor made sure that entire sections of the building had to be rebuilt: a circumferential joint had not met exactly. The monolithic building, which was listed as a historical monument just two years after its opening, lives above all from the joints in the ceilings and between the space-forming blocks, which are clad with horizontally layered slabs of green-grey Vals gneiss. The precisely placed gaps are necessary for structural reasons on the one hand, but as glass-covered light joints they also ensure the play of incident daylight, which gives the interior its characteristic structure in the first place.

What may appear to some as a banal gap, as mere nothingness, is one of the most important formal aesthetic elements in architecture and design: Joints connect or separate the different areas and materials of a design, they divide volumes as light or shadow joints and lend structure, they ensure precision or ambiguity. In the "theory of product language", the joint plays an important role: as an indication, the shape of a shadow gap on a rotary switch, for example, visualizes whether it can only be turned or also pressed. We use joints dozens of times a day to interpret how firmly we have to press a button, how loosely or stably elements are connected to each other, in which direction a door can be opened or how cleanly a product is manufactured. Joints convey information and make things tangible and "human".

The fascination with the precisely placed fugue has increased again in recent years.

Whether the various elements of a design are visibly or invisibly joined together can be considered one of the major themes of early 20th century modern design: The connection of two wooden surfaces with dovetail or finger joints had previously been concealed under veneer as a matter of course. Now, on the other hand, the construction was presented confidently and provocatively, in line with the well-known maxim that form should follow function. For example, the emphatically simple wooden stools from the 1950s by Le Corbusier or the "Ulm Stool" by Max Bill, Hans Gugelot and Paul Hildinger with their open tines became statements of modernity. As early as the 19th century, the term "material justice" referred to the aspiration to process and combine materials in a way that corresponds to their inherent material qualities - and to make this combination visible accordingly. It can therefore be seen all the more as a late provocation against the ideas of functionalism when the Dutch designer Hella Jongerius unceremoniously joins the two individual parts of her vases "Long Neck Bottle" and "Groove Bottle", designed around 2000, with "Fragile" adhesive tape because glass and ceramic cannot be joined together due to their different melting points.

And yet the fascination for the details of a perfect connection, for the precisely placed joint, has increased again in recent years. When the thick silicone sausage on our washbasins closes the last gap as standard, a masterfully executed joint once again becomes a subtle code for a quality of craftsmanship that was thought to have been lost. It is therefore not uncommon to see an architect or designer in public buildings painting over a particularly successful joint between two materials. Or you can see them kneeling curiously on the floor to admire the joint that opens up between the wall and the floor, where in normal homes only a standard skirting board conceals the frayed edge of a hastily laid parquet or drywall.

An art in itself: traditional wood joints

First the grout pattern designed, then the tile: Bottone" collection by Ronan Bouroullec for Mutina

The beauty of connections: architect Carlo Scarpa's former Olivetti store in Venice

The joint visualizes that the materials of a product can be separated and recycled.

In Instagram reels, we marvel at the incredible precision of Japanese wood joints, where the joints disappear completely at the last moment of joining. We rediscover the beauty of joints in Carlo Scarpa's designs from the 1950s or 1960s, such as his famous Olivetti showroom in Venice, where the space in between is just as highly valued as the precious materials. Or we are fascinated by the fact that the French designer Ronan Bouroullec first designed the grout pattern for Mutina before turning it into his "Osso & Bottone" tile collection. The supposedly inconspicuous joint is also attracting new attention in the context of sustainability issues: it has the task of unmistakably visualizing that the various elements or materials of a product can be separated and recycled according to type. Or that a product has a deliberately modular design, that it can be extended or replaced. In terms of sustainability, not only a visible screw connection, but also a joint becomes a sign of dismantlability or reparability. And so the joint once again becomes a quality feature in our time, a gap as an expression of conscious design and the beauty of the space in between.

Images: Fabrice Fouillet, Gerrit Schreurs, Alamy / Fergus Coyle, Andrea Osti, Mutina / Gerhardt Kellermann

Matching

Ulmer stool Max Bill

The Ulm Stool was designed in 1955 by Max Bill, the first director of the Ulm School of Design, in collaboration with Hans Gugelot and Paul Hildinger for the students of the same school. "Two vertical boards, one horizontal board, the three firmly interlocked, held together at the bottom by a round wooden rod", is how a contemporary described the construction principle of the stool. It was intended to serve as a seat, side table, shelf and carrying aid for the books needed for studying. It still does that today. It is made in Switzerland, using the same materials as the original.

More interesting facts

It is welcome on vintage furniture, but not so much on plastic objects: patina tells stories of the past and strengthens our bond with objects.

In der Halle, im Cluster oder gar im Haus aus dem Drucker – das sind nur drei von vielen Antworten auf die brandaktuelle Frage, wie das Wohnen der Zukunft aussehen könnte.

Time for a thought experiment! What if plastics were a valuable resource - and not endlessly and cheaply available?