Michael von Matuschka

Research on demand

When architect and designer Michael von Matuschka designs, he is not concerned with aesthetic self-realization, but with the question of how we actually want to live. The result is rooms and furniture that do justice to the complex everyday life in a community.

Text: Bettina Homann

People drink their morning cappuccino in the cafés, practise sun salutations in the yoga studio and carefully carry a pane of glass from the glassworks. Oderberger Strasse in Berlin's Prenzlauer Berg district is a place where living, working and leisure are close together. With its gray-brown façade, the narrow building right next to the Stadtbad, which has been converted into a hotel, looks quite inconspicuous at first glance. At second glance, however, the tiny exhibition space with its shop window facing the street and the large studio windows on the second floor arouse curiosity. From the stairwell with its bright yellow banister, you can catch a glimpse of one of the apartments: Walls made of exposed concrete, a high room with a gallery, a wall full of books.

All the apartments have several levels, almost all of them consist of a larger and a smaller part, both of which are accessible from the stairwell. This not only creates a special feeling of living, it also means that the smaller part can easily be separated off and converted into a separate apartment, for example when adult children move out. On the second floor, commercial space offers room to work, while on the first floor, stores and restaurants open up the building to the street. Oderberger Strasse 56 is essentially a kind of case study that explores how a building can meet complex urban needs.

The second floor houses the office of BAR-Architekten, who built the building in 2010. Michael von Matuschka founded the "Base for Architecture and Research" in 1992 together with fellow students Antje Buchholz, Jack Burnett-Stuart and Jürgen Patzak-Poor. This is definitely not a show-off office. The room is just under 40 square meters in size, with plain white wooden panels serving as desks. On a shelf in front of the large window facing the street are wooden building models like a miniature city.

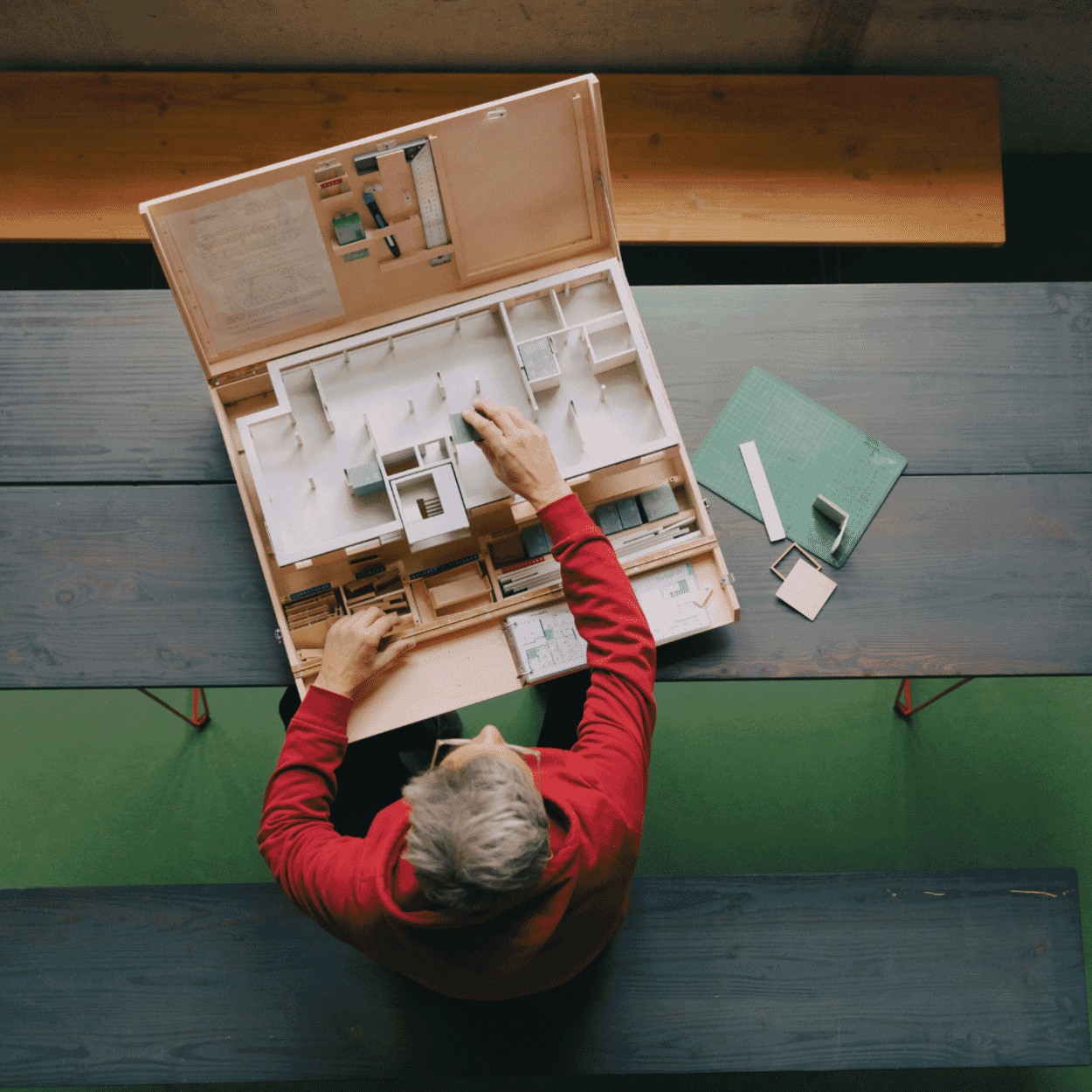

Michael Matuschka dispenses with the black turtleneck sweater and black horn-rimmed glasses that make some of his colleagues look like replicas of themselves. His glasses are light-colored and he wears a red hoodie with dark blue work trousers. To explain how the BAR team works, he grabs a kind of plywood case from the shelf. If you open it up, you can see a miniature version of an apartment from above. "We all moved into these unrenovated apartments shortly after reunification. Most of them didn't have a bathroom. When the housing associations started installing bathrooms, we found that they were actually making the floor plans of the apartments worse," explains Matuschka. That's why they developed the idea of the walk-through bathroom. In the model, Matuschka shows how a hallway can be transformed into a bathroom by closing two doors. The result is a room that can be used in different ways depending on requirements. This first project already makes the BAR program clear: it is about researching the complex needs of people in urban spaces and developing solutions that meet them. Matuschka speaks calmly and with concentration, a man who means business. Only occasionally does a small grin flit across his face beneath his thick, gray mop of hair, making him appear boyish. He doesn't make any grand gestures, his hands are busy pointing out details in the model.

Models have been an essential part of the architectural team's work since they studied under William Firebrace at the Berlin University of the Arts (now Berlin University of the Arts). Firebrace taught the students to develop spatial concepts from the observation of existing contexts. Building prototypes played a major role in this. "Above all, models serve communication, the joint development of solutions, comprehension in the truest sense of the word," says Matuschka.

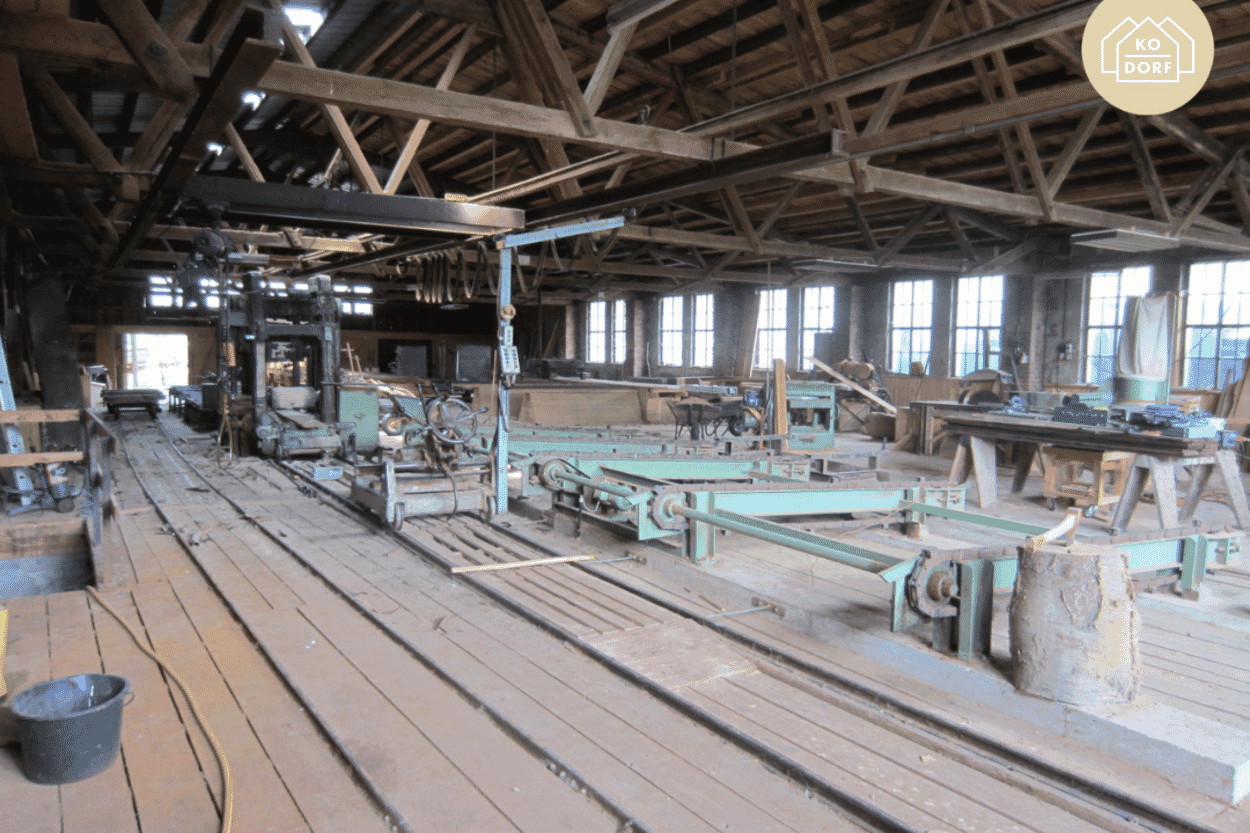

However, the 58-year-old has always enjoyed making things, ever since he built a series of yo-yos in the school's wood workshop in his final year. "Those were my first attempts at design." It was clear to the young man that he wanted to continue in this direction. He completed a carpentry apprenticeship near Bamberg and then studied industrial design in Essen and Vienna. There he met many architecture students. "I thought to myself that as an architect I could also be a furniture maker, but not the other way around." After convincing his father to finance his further studies, he moved to Berlin. Matuschka still likes to lend a hand today, for example on the current BAR project, the conversion of a row of garages in Berlin-Wedding into a residential-commercial complex. He doesn't wear his work trousers for fun.

Even to the trained ear, there is no regional inflection in Matuschka's language that would indicate where he grew up. "No dialect, no home," is the Hessian saying. In a way, this applies to Matuschka. His father was in the diplomatic service and the family moved around a lot. He was born in Salzburg, spent a few years in Pakistan, Tokyo and finally in New York. But what remained the same despite all the changes of location was the furniture. "In a way, the furniture was our home," says Matuschka. What he particularly likes are the Japanese Tansu chests of drawers. "They are not only very beautiful, but also very flexible. They work like moving boxes when needed, as you can fold down the fittings and push a bar through to carry them."

Flexibility and adaptability also characterize Matuschka's own furniture designs, which are manufactured by MAGAZIN. For BTB, he was inspired by the classic beer bench set. The furniture consists of a wooden top and a steel frame with legs of different lengths. Depending on how it is attached, a table or a bench is created. LTL works on the same principle: a table that can be "lowered" and transformed into a guest bed with an overlay. The layered wooden panels are reminiscent of construction timber in their workmanship. "I was thinking more in a work context during development," says Matuschka, explaining the design. But of course they are also suitable for unexpected visitors or a quick garden party. This furniture doesn't want to be the center of attention and doesn't mind being stacked in the cellar. But they are certainly admirable - simply because they are so perfectly thought out.

At the end of the visit, Matuschka takes visitors to the workshop in the basement. "The workshop is simply part of it," he says. This is where the old circular saw that has accompanied the BAR team from the very beginning is located. This is also where the cabinet made of a wooden frame and thin MDF boards stands, which was actually supposed to be included in the MAGAZIN program. However, this never happened. "Somewhere along the way, our ideas diverged," says Matuschka. He doesn't seem particularly frustrated about it. In a world of lived complexity, failure is not a failure, but a step in development.

Pictures: Lena Giovanazzi

MICHAEL VON MATUSCHKA FOR MAGAZIN

BTB & LTL

More about the future of living

In the hall, in the cluster or even in the house from the printer - these are just three of many answers to the burning question of what the housing of the future could look like. Instead of standard floor plans and concrete castles, we need more variable, diverse and environmentally friendly living space.

Frederik Fischer is convinced that the future lies in the countryside. He is the initiator of the "Summer of Pioneers", a network that enables trial living in rural areas, advises local authorities on how they can make life in the countryside attractive to stressed city dwellers and plans so-called co-villages.

.png?profile=kuratorteaser_32)

.png?profile=kuratorteaser_1250)