Entering the age of wood

Wood is the material of the moment, promising climate-friendly growth without regrets. But how did this commonplace material become the ultimate beacon of hope in such a short space of time? And what are the consequences when a slow-growing resource is suddenly in such demand? A search for clues between high-rise timber buildings, overexploitation in the forest and the special charm of German hobby cellars.

Text: Stephan Becker

In the world of fashion, it is part of everyday life that trends come and go. But in the world of building materials? Not so much. Sure, plastic used to have a better reputation, and concrete is also struggling at the moment. But that makes little difference to their actual consumption. After all, what counts are their specific qualities. Only wood and its derivatives seem to be different. For decades, it was primarily in demand as a material for simple constructions, cheap furniture and cozy parlors, but it is now downright modern - with a steep rise in demand. No other material, it has to be said, is currently better suited to the needs and zeitgeist. What has happened?

RELIABLE WORKHORSE

Until a few years ago, wood was a rather unexciting material. Presumably in use since the beginning of human history - think of the stylized primitive hut by the Roman architectural theorist Vitruvius - it was for a long time the ultimate all-purpose material for dwellings, means of transport, furniture and even tableware. Certainly, iron and bronze have shaped their own epochs with their names. But wood? It was never in the front row as a workhorse. All-round reliable, often solid and sometimes even innovative - think of the laminated wood experiments of the mid-century style, for example - but rarely en vogue.

All hope in wood

This has changed radically in the last few years. This can be seen not only in the photo spreads of architecture and interior design magazines, but also in the fact that politicians have discovered the topic for themselves. If you want to be progressive, you adorn yourself with wood, and climate change is of course a key aspect of this. After all, the construction industry is one of the main emitters of greenhouse gases. And it could help that wood is the only building material used in large quantities that binds CO2 during production - i.e. in the forest. And this CO2 remains bound as long as a building stands, like a second forest of houses. This is one of the reasons why the renowned climate researcher Hans Joachim Schellnhuber and the "Bauhaus der Erde" initiative, which he co-founded, are calling for an architectural movement that focuses on timber construction.

PIONEERING WORK ON THE BUILDING CODE

Wood was of course always in use as a building material. After all, half of the American suburbs are made up of simple frame houses. And we still have many cozy prefabricated wooden house from the seventies. But in an urban context, timber had a difficult time for a long time, which may have been due to the odd medieval fire. Wrongly, however, as some timber construction pioneers emphasized around twenty years ago, who were even able to bring about a change of direction in building legislation with their experimental buildings. This is because timber is actually a material that is extremely easy to calculate, especially when it comes to fire protection issues.

Espacially compact cross-laminated timber components , usually prefabricated into thick panels in the factory, only char on the surface and are then well protected. And from a structural point of view, timber constructions are beyond reproach anyway, as half-timbered houses in every German old town show. Today, multi-storey residential buildings have long been standard in building regulations and often even go much higher. In Sweden, for example, a high-rise building with eighteen storeys was built two years ago, which is largely made of wood. And in such exceptional examples, the highlight is often not just the climate friendliness of the material. Thanks to numerous innovations, particularly with regard to its processing, wood is usually also a good choice when things need to be done quickly, quietly and cleanly. Where carpenters may have had to lend a hand in the past, today computer-controlled milling machines in the prefabrication plant often do most of the work.

Beyond tongue and groove

The fact that Scandinavia in particular plays a pioneering role in timber construction should come as no surprise to anyone given its extensive forest regions. In view of the material's changing image, however, this is proving to be an advantage in aesthetic terms. The cozy, deep tongue-and-groove charm of German hobby cellars or the chalet style of the Alpine countries would certainly not have been a suitable model. Scandinavian interior architects and designers, on the other hand, show how wood as an interior material conveys modernity and style and leaves bourgeois hygge cosiness behind.

The interactions between architecture and furniture construction are not only interesting from an aesthetic point of view. They are also and above all decisive in terms of workmanship and construction. Doesn't furniture construction sometimes even seem to drive architecture, if you look at the experimental lightweight pavilion for the Federal Garden Show in Heilbronn by Achim Menges and Jan Knippers, for example? Not only is it characterized by a particularly high level of material efficiency, its panel skin also looks a little like chair parts have been used here. Conversely, the design also benefits, because where wooden furniture often looked rather heavy in the past, surprisingly light-footed objects are now possible thanks to high-performance panel materials and bending and joining techniques. As early as the 1990s, designers such as Axel Kufus developed furniture types - such as the FNP shelving system - that express their own constructive aesthetics with a minimalist use of materials and plywood panels.

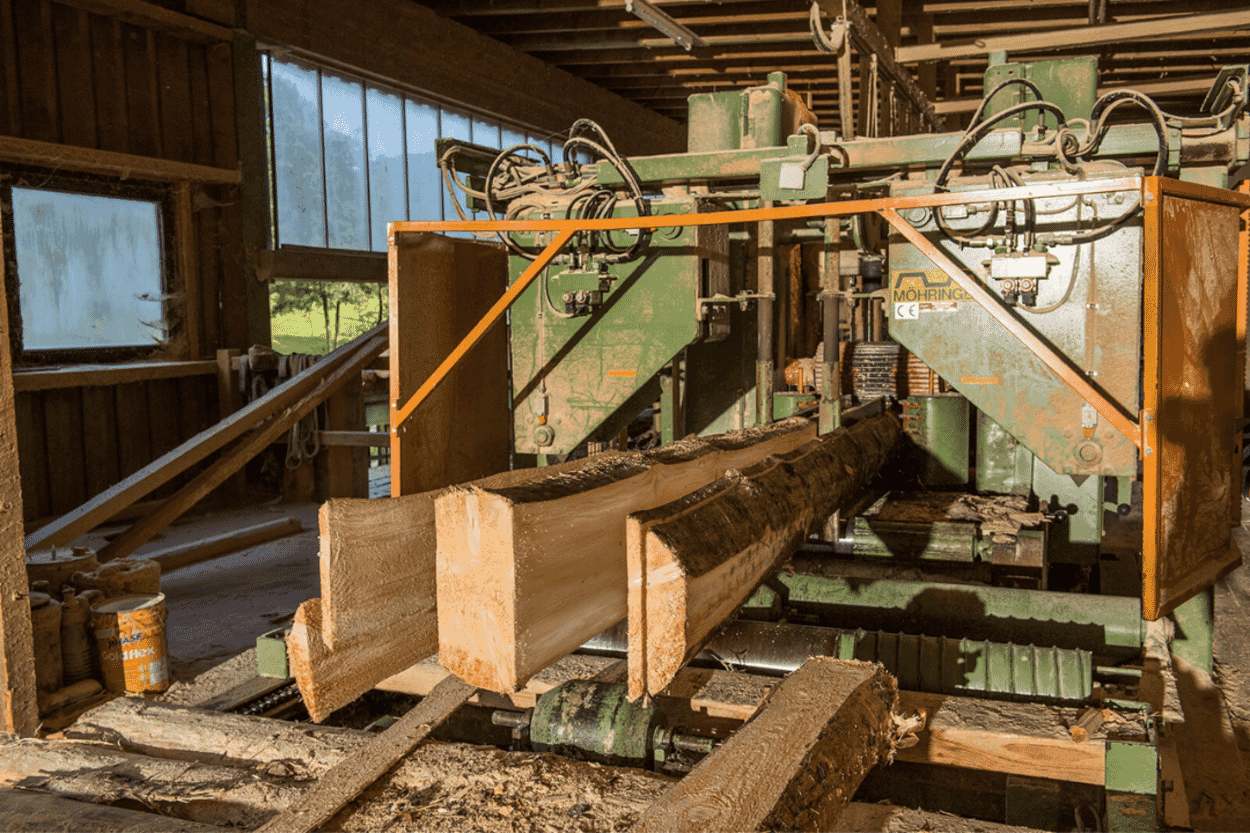

Overexploitation for chipboard

However, every fashion has its downsides, and it is worth taking another look at the furniture industry. Wood-based materials dominate even when a wooden surface is not required. Wood-based panel materials not only have a number of advantageous properties for construction, but are often cheaper than solid wood. Just think of the ubiquitous chipboard, which is not only used in countless kitchens, but can also be found under many a cosy sofa.

As a result, usage patterns are also changing. While our grandparents' sofas may have lasted a lifetime, in view of their price and durability, we can now talk about fast furniture, analogous to cheap fashion that is thrown away after a short time. And there, at the latest, thick layers of lacquer, PVC coatings and, of course, the glue that holds the wood chips together become a problem that usually ends up in the waste incineration plant - with all the disadvantages for the climate. What's more, with the greatly accelerated purchasing cycles, the demand for wood has also increased to such an extent that illegal overexploitation of protected forests is repeatedly coming to light.

Leave the tree in the forest

Illegal deforestation is less of a problem in architecture, as complete quality control is required here for structural reasons alone. But here too, the overuse of certain species or the spread of timber monocultures cause ecological problems. Sustainable timber management, as promised by the FSC seal, can help to achieve climate targets and avoid conflicts with other ecological requirements, such as biodiversity or water conservation. But for Torsten Welle from the Naturwald Akademie, which deals with ecological silviculture among other things, it remains a simple truth: the existing forest is the best store for carbon dioxide.

Avoidance therefore always comes before consumption, stock always before replacement, and if something new is built or bought from wood, it should be used for as long as possible - a plea for solutions that are as high-quality as they are beautiful, for adaptable and flexible solutions that we still enjoy using even after a long time. It is also important to remember that there is no such thing as one ideal material. Good old steel, for example, has its advantages for many applications, not least because of its recyclability.

REINVENTING A MATERIAL

Despite all the challenges, we must not forget one key aspect of the current wood boom: That it is not the result of a superficial fashion, but driven by a genuine search by many clever people for sustainable solutions. This also includes efforts to achieve a new constructive honesty in architecture, as made possible by timber construction, without insulation and cladding, but with maximum recyclability.

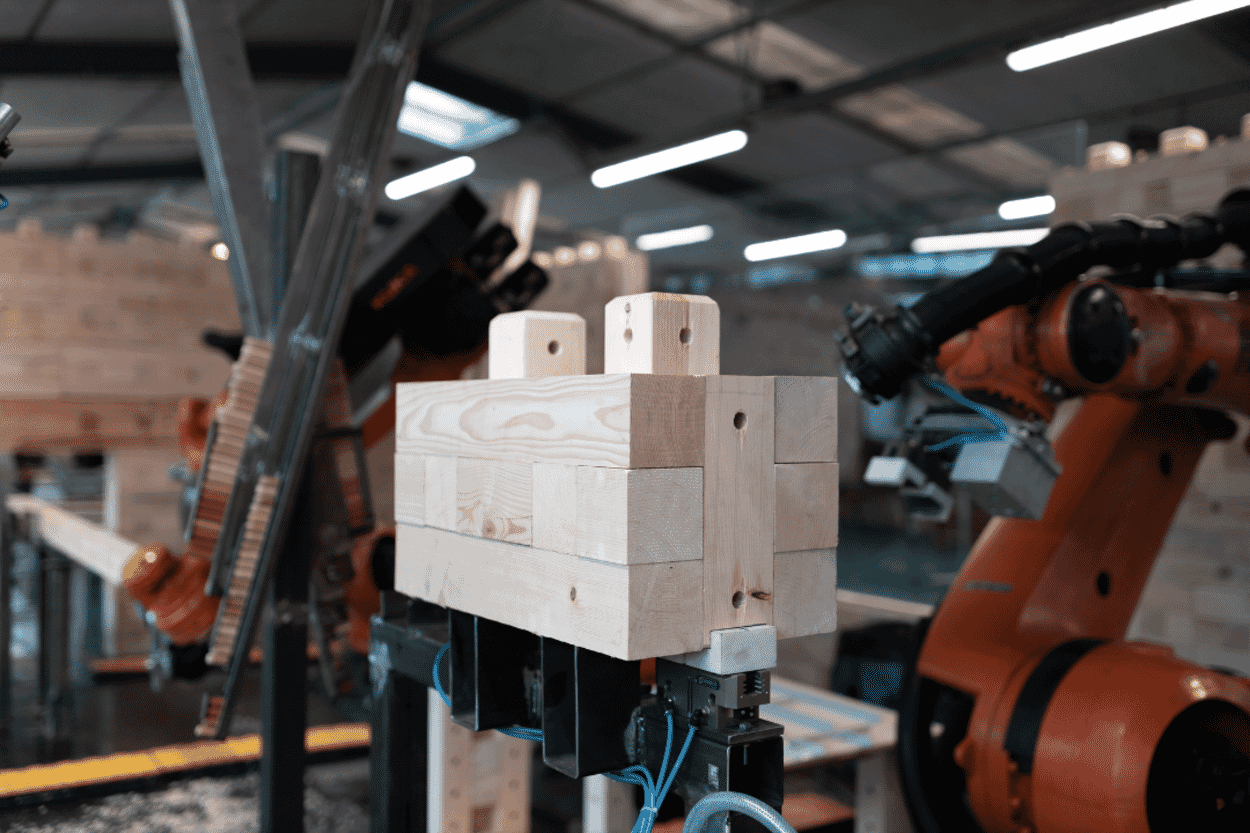

This also includes new panel materials from the wood industry that are manufactured using only natural resins. And finally, start-ups such as Triqbriq from Stuttgart, which uses industrial robots to produce solid wood building blocks from low-quality calamity wood - the result of pest infestation, storms or drought - that could be used to build multi-storey "walls" in the future.

In short: we are experiencing the next chapter of a material that is thousands of years old and whose use is currently being expanded with a great deal of creativity and a clear goal in mind to create fascinating possibilities.

Pictures: Woodcut: Unsplash @theforestbirds; ICD/ITKE; Voll Arkitekter AS; Kai Nakamura; TRIQBRIQ AG; Photographers Martin-Diepold

MORE ABOUT WOOD

When it comes to materials in architecture, there is not just one truth. Zurich architect and university lecturer Elli Mosayebi and her firm Edelaar Mosayebi Inderbitzin Architekt*innen focus on the specific advantages of a building material in relation to the design idea.

Wood is wood? Not at all! In furniture construction, there is a whole range of materials based on this renewable raw material. Here we present five of the most common materials - from solid wood to multiplex.

Designers and thinkers Enzo Mari and Victor Papanek were already interested in building furniture themselves and making the world a little better. Japanese architect Keiji Ashizawa has taken the idea a little further.