We should deal with things more consciously

Mattresses crumble, computer cases turn yellow, coatings become sticky: plastics may be considered durable, but they age just like any other material. Tim Bechthold, restorer at Munich's Die Neue Sammlung design museum, explains how plastics degrade and which piece of furniture is his biggest problem child.

Text: Jasmin Jouhar

How did you come to specialize in plastics - that was rather unusual?

I've always loved going to flea markets, and I was particularly enthusiastic about furniture from the 60s and 70s. There was a lot of experimentation with plastics back then. During my studies, I had the opportunity to concentrate on this.

Plastics are considered to be stable and easy to care for. But why do they still age?

You can't talk about plastics in general. There are plastics that are more stable than wood when exposed to the weather. But there are also plastics that disintegrate almost as soon as you look at them. First and foremost, it is external influences such as light or oxygen that cause plastics to age. The polymer chains that make up all plastics are chemically transformed. This can sometimes lead to the familiar discoloration, for example when the white housings of computers turn yellowish-brown.

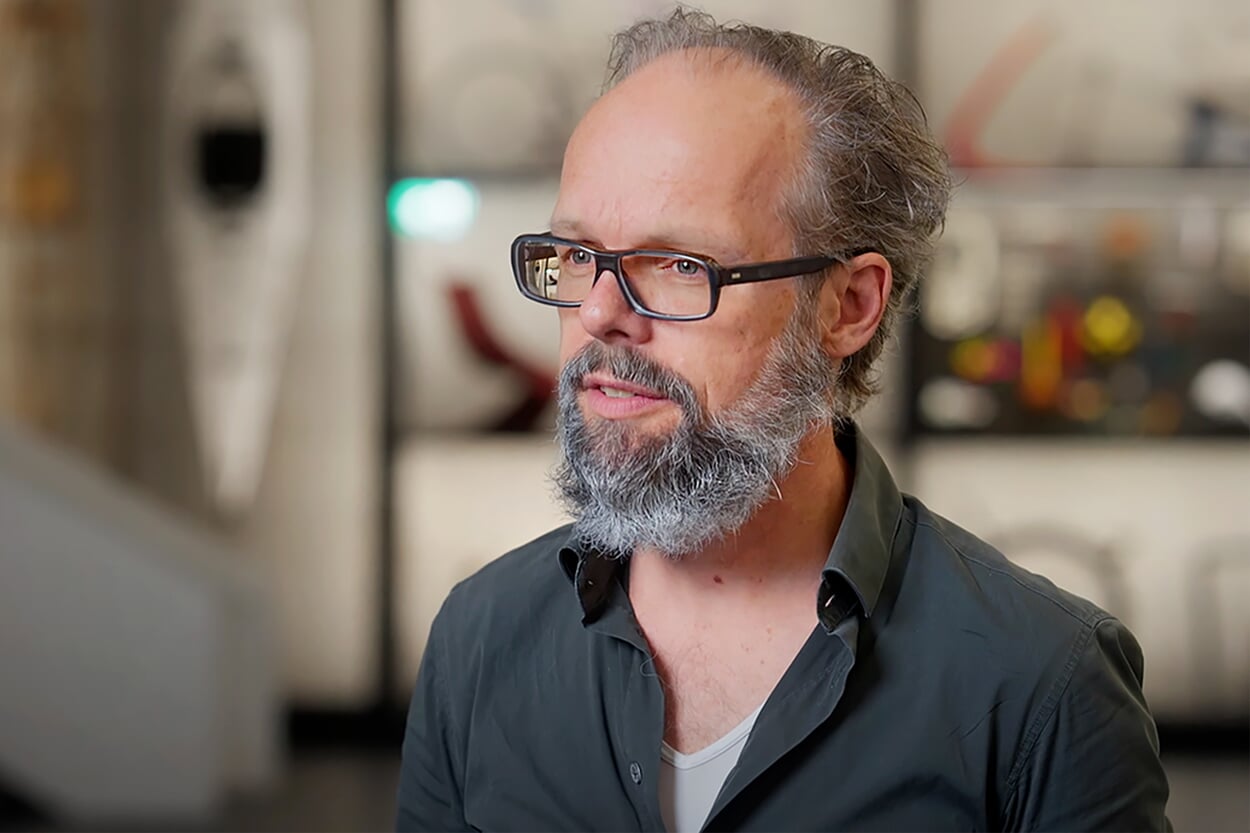

Tim Brechthold

Tim Bechthold has been head of the restoration department at the Munich design museum Die Neue Sammlung since 2002 and specializes in plastics. After training as a carpenter and furniture restorer, he studied restoration and conservation science at the Technical University of Munich and graduated with a degree in polyurethane in 1960s furniture design.

Are there other examples of ageing processes that everyone is familiar with?

For example, those thin, rubbery coatings on razors, cell phones and household appliances. They feel very grippy at first. But they become sticky within a relatively short time. Or take the soft foams that make up mattresses, for example. If such foams are not protected by a textile or coating, they turn brown very quickly and then become brittle. To generalize, you could say that plastics that are very thin, plastics that have very large surfaces, are predestined for ageing processes. Light and oxygen, for example, can then attack the plastic polymer easily and extensively and damage it accordingly. However, there are major differences in quality, for example with plasticized PVC. If you choose more expensive films here, you can assume that they will last longer. Another aspect is the intended service life of a product. If, as with cell phones, a market presence of only one to two years is planned, then manufacturers will hardly use high-quality plastics. In comparison, a significantly longer service life can be expected from the serial production of high-quality plastic furniture. Such products are usually extensively tested and the plastics are additionally stabilized with additives such as UV absorbers.

How many plastic objects do you have in the museum's collection?

In total, we have an estimated 120,000 objects in the collection. But we don't know how many of them are made of plastic; we don't collect any figures on this. Many objects from the 20th century definitely contain some kind of plastic part.

What is the biggest problem child in the collection whose decline you cannot stop?

One of the biggest problem children is the "Tube Chair" by Joe Colombo. The seat tubes are upholstered with polyurethane foam covered with a thin "wet-look" coating. The material is subject to heavy blooming, or to be more precise, salts crystallize out as a result of the chemical degradation processes and the material becomes brittle. Although we can remove the crystallization products, we have no means of preventing the efflorescence process. The surface is so fragile that we can't apply a protective coating.

And an example of a piece that you were able to save?

For example, a fiberglass couch by Luigi Colani. It came into our collection with a lot of damage. We bought it anyway because it came from a small series and only a few of them have survived. The previous owners had caused the drastic damage when they tried to clean the surface with improper means. It was badly corroded and broken open in sections. We applied a separating layer and then retouched it using airbrush technology. It was about finding the right balance between acceptable signs of ageing, which are part and parcel of furniture from 1968, and reducing the damage.

With your expertise, would you say that we should consume less plastic - if we think about microplastics, which are produced during decomposition processes?

I would agree, but only with regard to products made from cheap plastic. It can be different, even more sustainable, with a high-quality plastic chair that lasts longer and is even passed on thanks to its good design. And then there are the materials where you don't even think of plastic, such as chipboard, which usually contains synthetic resins as a binding agent. A big problem when it comes to disposal. I think we should simply be more aware of how we use things. My mother used plastic dishes and appliances for decades. We think differently today. If something gets stained, we quickly buy something new. I can't exempt myself from that.

Images: © Die Neue Sammlung - The Design Museum, Photo: Tim Bechthold; © Die Neue Sammlung - The Design Museum, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gYXUVkpy5Cc

More on the subject of plastic

Time for a thought experiment! What if plastics were a valuable resource - and not endlessly and cheaply available? This change of perspective could help us break free from our toxic relationship with plastic. The goal: to consume plastics more consciously - away from single-use, towards long-term use, away from packaging that is quickly disposed of, towards sensible, recyclable plastic products.

Everyone should be aware by now of how destructive the unbridled production and use of petroleum-based plastic can be. That is why alternatives have long been researched. In their studio in a former paint factory near Amsterdam, the duo Klarenbeek & Dros are working with algae and fungi on the plastic of the future. Not only should it be compostable and protect the environment, its production should also bind CO2 - and even promote biodiversity.

.png?profile=kuratorteaser_32)

.png?profile=kuratorteaser_1250)