Departure for Utopia

In the hall, in the cluster or even in a house from the printer - these are just three of many answers to the burning question of what the living of the future could look like. Because one thing is clear: instead of standard floor plans and concrete castles, we need more variable, diverse and environmentally friendly living space.

Text: Katharina Rudolph

"The most burning question of the day", said Walter Gropius, director of the Bauhaus in Weimar, in 1924, was: "How will we live, how will we settle, what forms of community will we strive for?" Today, one hundred years later, these topics are once again highly topical, albeit under different circumstances. After all, we cannot continue to build and live as before when even high earners can barely afford the rents in large cities and the population pressure on urban centers is constantly growing; when there are diverse forms of cohabitation - multi-generational households or single-parent shared flats - but our ever-same floor plans do not promote them at all; when private life and work are moving closer together, but most houses are not designed for this; when almost 40 percent of global CO2 emissions are attributable to the construction, operation and demolition of buildings and infrastructure, making the construction sector the "elephant in the climate room", according to climate researcher Hans Joachim Schellnhuber; in short, when our residential architecture is lagging far behind social and ecological developments. However, convincing answers as to how we can move towards a better future are still largely lacking.

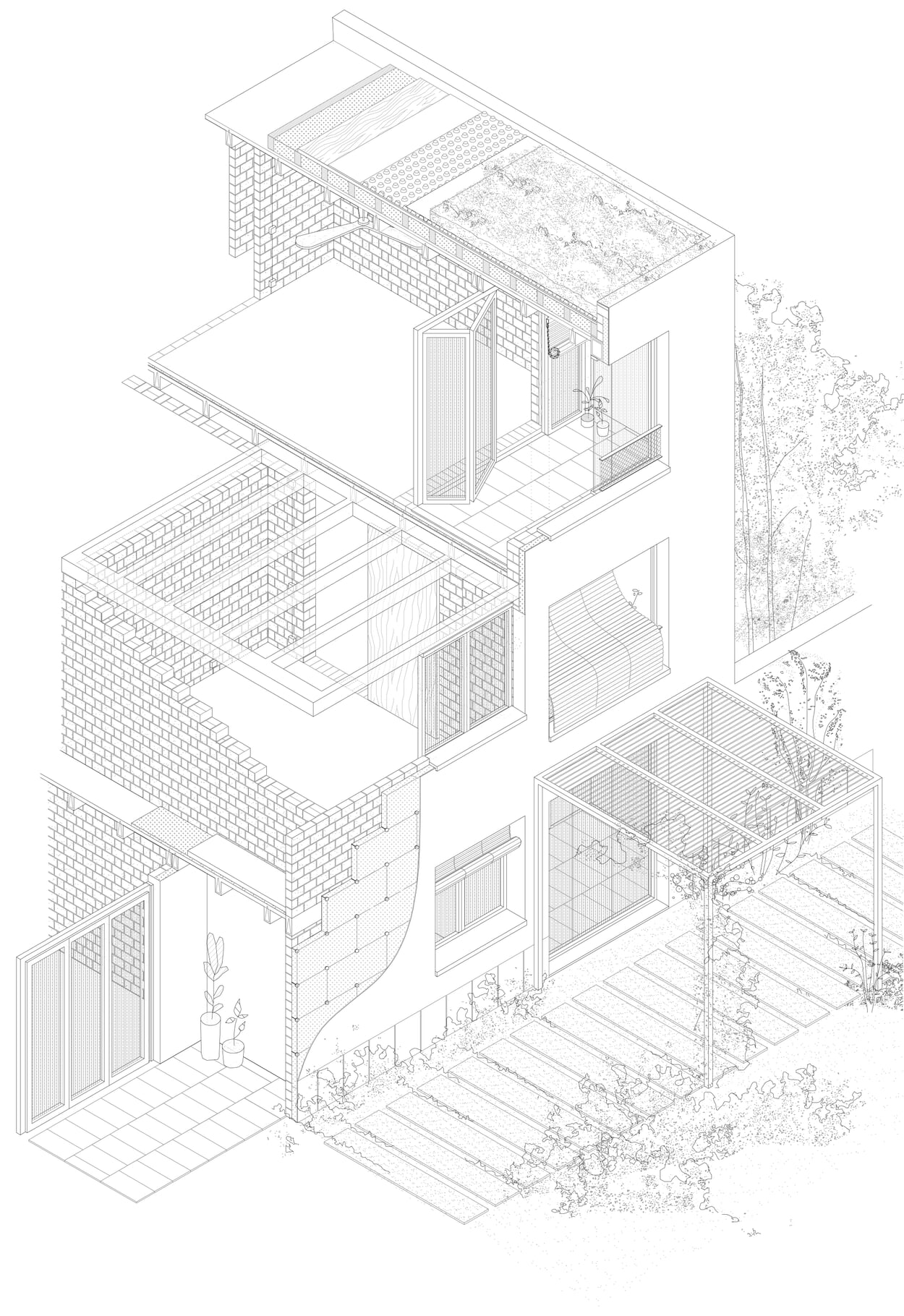

Some architects, citizens and researchers are daring to conduct bold experiments in order to redress the imbalance and counteract climate-hostile concrete apartment blocks and dull, uniform buildings. They are committed to ecological building, devising community-promoting concepts, colourful neighbourhoods, minimizing costs and developing innovative floor plans. So what could the housing of the future look like? Perhaps like what a cooperative in Hamburg is currently dreaming up. There, on the foundations of an old multi-storey parking lot in the middle of the old town, an innovative residential and work building oriented towards the common good is to be built, including cultural and gastronomic uses, a kind of vertical city in miniature. In terms of sustainability, the Gröninger Hof cooperative is killing two birds with one stone by using existing architecture on the one hand and building with the climate-friendly raw material wood on the other.

Originally, the building, designed by Swiss firm Duplex Architekten, was to be built on top of the former parking garage. However, chemical tests revealed that all above-ground components would have to be demolished. However, retaining the floor slab, foundations and basement walls saves 42 percent of the CO2 emissions that a conventional new building would have caused - an important finding for similar projects, as the wrecking ball usually rolls in far too quickly at present. The Hamburg project is also a prime example of new living because different housing typologies from one to six-person households are being created there, meaning there will be well-designed, affordable space for many instead of overpriced monotony for a few. The design by Duplex Architekten follows the forward-looking strategy of minimizing private space and sharing everything that is not constantly needed - guest rooms, playrooms, sports rooms or offices - with the house community; for the sake of the climate, the wallet and social exchange. Young cooperatives in particular are doing pioneering work in many places in this respect, because they are looking at the housing of tomorrow beyond a profit-oriented construction industry and defending the right of every individual to participate in urban life with moderate rents despite rising building and land prices.

Another modern feature of the Gröninger Hof are the so-called cluster apartments, a form of co-living that has become increasingly popular in recent years because it does justice to the diverse living environments of a pluralistic society. An apartment consists of a cluster of small private rooms with bathrooms and sometimes kitchenettes as well as large communal areas. In contrast to conventional shared apartments, where collectives arrange themselves in apartments that are not designed for this (because they only have one bathroom, for example) due to a lack of alternatives, there is a more balanced relationship between proximity and distance here. At Gröninger Hof, not only students, but also couples, small families, older people and single parents will move into the cluster apartments, because the community promises support in everyday life. Living in clusters may be challenging, says Tina Unruh, deputy managing director of the Hamburg Chamber of Architects and member of the cooperative's supervisory board, but she is pleased to see how much interest there is and how much courage older people in particular have to give up a larger apartment "in order to live in significantly less private space in future - but with the knowledge that they will not be living alone". Across Germany, the living space required per person is over 47 square meters; the Gröninger Hof will end up with around 30 square meters for all residential units combined.

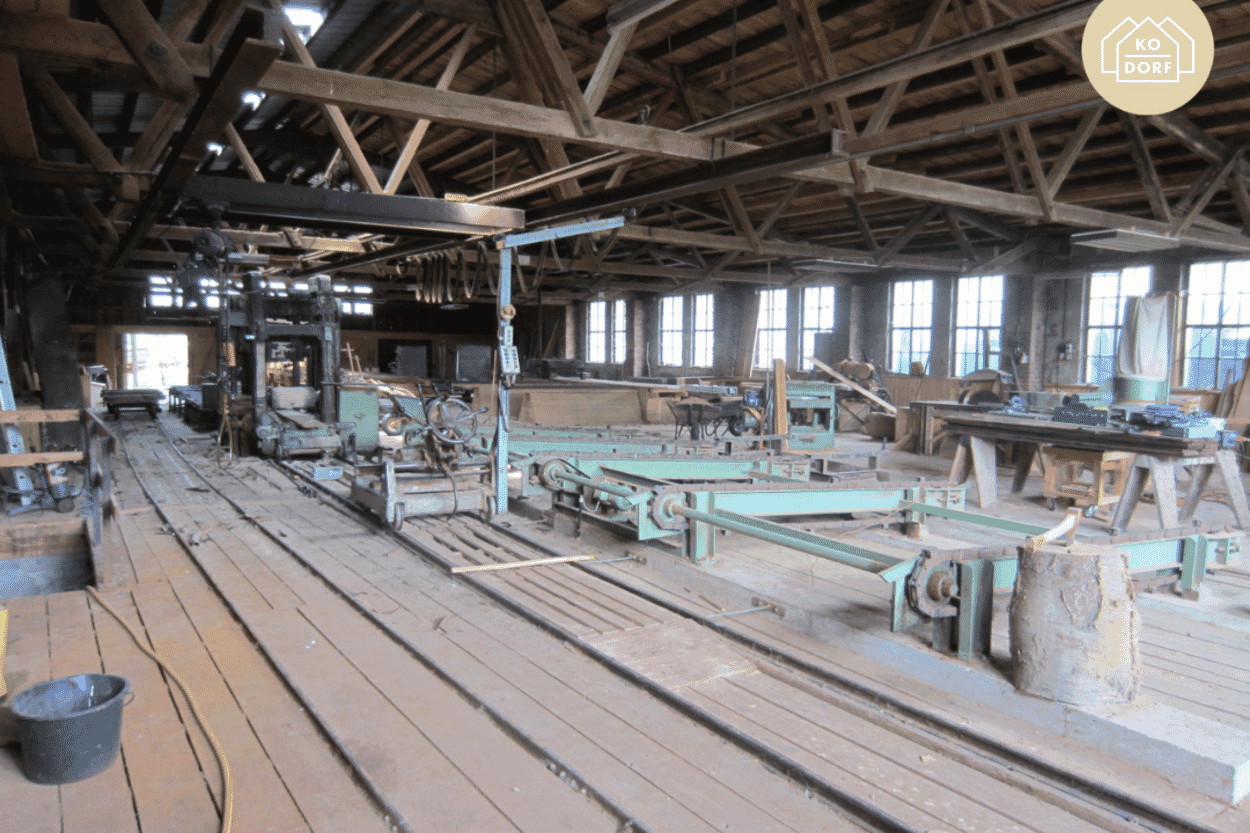

A particularly bold form of condensed living in a community is so-called hall living, which is not being tested in Hamburg, but in some Swiss projects. This involves a large group of people coming together - formerly semi-legally in empty commercial buildings, nowadays as part of cooperative projects - to move into an XL apartment without predetermined room layouts. They take over the shell of the unit, which is only equipped with a kitchen connection and sanitary facilities, and do the rest themselves. The residents creatively adapt the space in which they live and sometimes work according to their needs. Traditional rooms are replaced by open, fluid spaces. In the Zollhaus of the Kalkbreite cooperative in Zurich, which will be occupied in 2021, resourceful tenants have designed modular furniture for a four-metre-high, 260-square-metre hall that resembles a tiny house. The two-storey residential towers, which can be moved around the space and docked together, usually have sliding windows instead of walls and serve as private retreats.

Another trend that can be seen in many progressive projects is apartments that can be flexibly enlarged or reduced in size. In the Zollhaus, which also offers more conventional living typologies in addition to the Hallen-WGs, there are joker rooms that can be temporarily rented in addition to a unit; in an experimental settlement by French architect Sophie Delhay, which was built in Nantes in 2008 but is still radically modern, "plus rooms" were so cleverly positioned and constructed that they can be added to different units without much effort. If an adult child moves out of apartment X, the plus room can dock onto apartment Y, where a baby has been born. And in a project by the Viennese office AllesWirdGut, in which multi-family timber hybrid houses are being built for hundreds of people, the apartments are planned with an additional window that is not needed to provide them with sufficient light. This means that a bonus room can be separated off within your own four walls with simple means; as a home office or retreat for a carer. The future of living therefore also means: architecture is open and flexible, it adapts to the flow of life, not the other way around.

Peris+Toral from Barcelona impressively demonstrates that even in social housing, where the financial framework is tight, clever concepts for future construction can be created. Not only did they build Spain's first wooden social housing building - and were among the finalists for the Mies van der Rohe Award, the most important European architecture prize, in 2022 - but they also realized a social housing project on Ibiza that is largely made of clay. Clay has an excellent carbon footprint, is completely recyclable, is available in abundance almost everywhere on our planet and, in the case of the Ibiza building, is an excellent building material when pressed into compact bricks. The fact that the use of a centuries-old material that is still underestimated in this country can even be combined with ultra-modern technology is demonstrated by the work of Italian architect Mario Cucinella, who, together with the company WASP, which produces 3D printers, has had the prototype of a cosy two-room hut made of clay printed; an entire eco-village could be created from several of these archaic-futuristic dwellings.

Whether in a house from the printer, in a cluster or even in a hall - the living of tomorrow will be one thing above all: colourful. Because social diversity urgently needs structural diversity. Just like a hundred years ago, in the days of the Bauhaus, building culture must reinvent itself. The pressure is high, because we can no longer afford the houses we live in today in view of the climate crisis. The visionary projects of the present point the right way; towards a better, socially and ecologically sustainable future - because a good life also needs good architecture.

Images: Unsplash @theforestbirds; ICD/ITKE, University of Stuttgart; Voll Arkitekter AS; Kai Nakamura; Peris+Toral

More about the future of living

When architect and designer Michael von Matuschka designs, he is not concerned with aesthetic self-realization, but with the question of how we actually want to live. The result is rooms and furniture that do justice to the complex everyday life in a community.

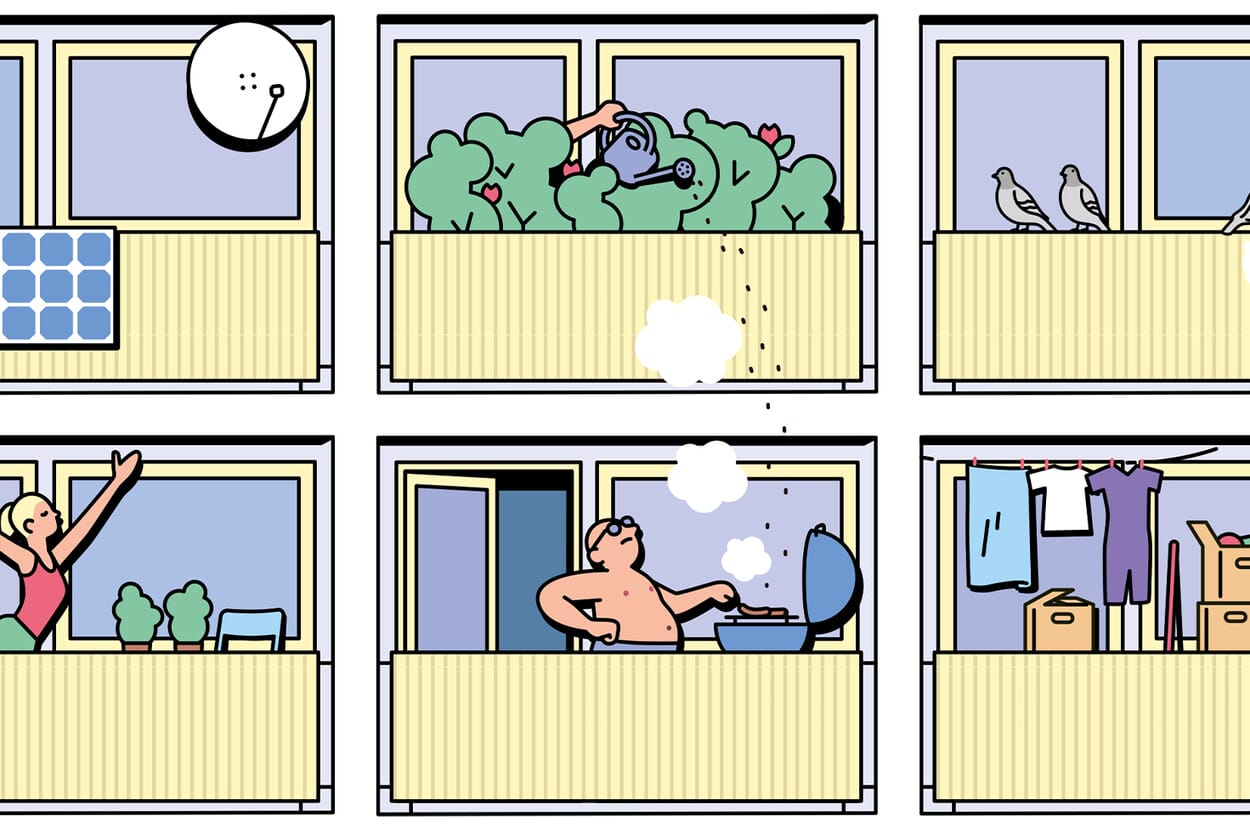

A balcony would be great! That's what every second apartment advertisement says as a hopeful final chord. Everyone wants one. But unlike a bathtub, the best balcony is always the one you don't have yet.

Frederik Fischer is convinced that the future lies in the countryside. He is the initiator of the "Summer of Pioneers", a network that enables trial living in rural areas, advises local authorities on how they can make life in the countryside attractive to stressed city dwellers and plans so-called co-villages.

.png?profile=kuratorteaser_32)

.png?profile=kuratorteaser_1250)